A year and a half ago, I had a conversation that changed the course of my business and my life. I was talking to a friend about efforts Two Octobers was making to be more intentional about diversity and inclusion. I mentioned that we were reevaluating how we recruit candidates, and her response was blunt: “your system is broken”.

In Switzerland, where she lives, most people enter professions and careers through apprenticeship. Contrast that with the US, where a person is expected to pay their own way through school with no guarantee of employment. In fact, schools are typically so detached from the working world that we describe graduates as “entry level” and pay them accordingly (if we hire them at all).

In the apprenticeship system, employers, schools and workforce organizations partner together to identify and cultivate the skills that are in-demand. Apprentices work and study in their chosen field at the same time. Their apprenticeship is complete when they have demonstrated to their employer that they are ready to move to the next level.

A year and a half after that initial conversation, I can say that creating an apprenticeship program is not all that hard to do, and it really works.

The Problems

I believe that apprenticeships should exist in all professions, but I am most qualified to speak to the problems they solve in my field: marketing and advertising. Two stand out:

- As a profession, we are not diverse in any sense of the word. This is a social problem and it affects the quality of our work. A business hires marketers to connect with all potential and current customers, but homogenous marketing teams are mostly good at connecting with people like them.

- Hiring is hard. Simply put, the supply of qualified candidates does not meet the demand (Andrew Seaman, 2021). The disconnect between what marketing students learn and what employers need is profound.

Diversity in the field of marketing

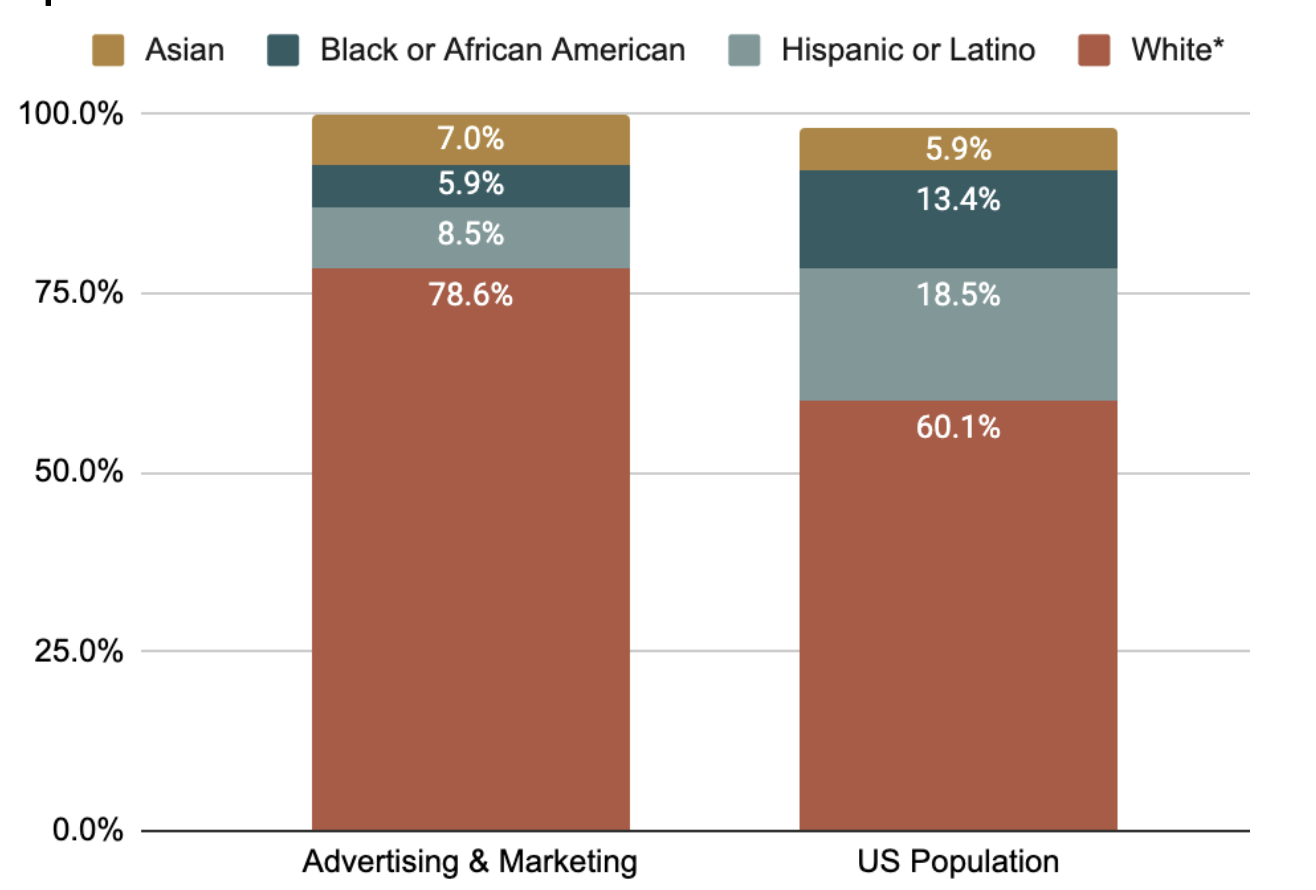

Below is a chart comparing the racial diversity of our profession to the US as a whole. People who describe themselves as Hispanic, Latino, Black or African American comprise 14.4% of advertising and marketing professionals. That same group represents 31.9% of the US population. Anecdotally, I can say that we don’t do any better in terms of socio-economics, abilities, military service or other measures of diversity. Given that most professional jobs require experience, these are not problems that can be solved by blinding resumes or changing your recruiting practices. As the statistics show, the pool of experienced candidates is biased. The only way to change the numbers is to create new opportunities for underrepresented groups.

Diversity in Marketing & Advertising Jobs Compared to the US Population

*Non-hispanic

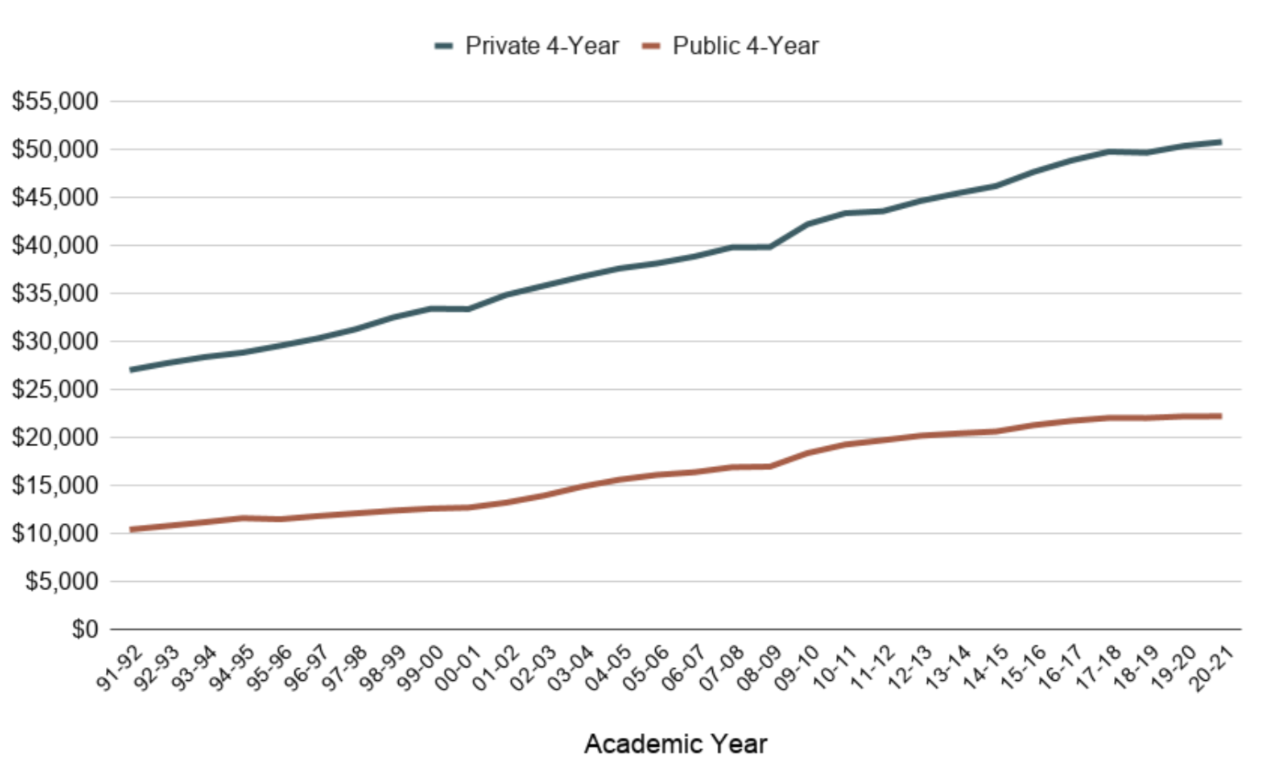

Another fundamental issue is the expectation that entry-level candidates have a four-year degree. Below is a trendline of college tuition since 1991. College was never cheap, but it’s getting more expensive every year. Requiring a college degree is a compound issue. It directly impacts the socioeconomic demographics of our profession, but it also correlates to biases against other underrepresented groups.

Annual College Tuition, Room & Board by Year

In some careers, a degree requirement makes more sense. Engineers, for example, need a degree for professional certification, and much of their education is focused on skills they will use on the job. This is generally not true with marketing. I am an adjunct professor of marketing, and I receive consistent positive feedback from my students that mine is one of few classes that will help them to get and succeed at a job, because of the practical skills I teach.

The pool of qualified candidates

This gets to the second key issue apprenticeship solves: hiring is hard. The demand for people with current and relevant marketing skills is growing, while university programs tend to put emphasis on research skills and marketing concepts. I love research and concepts, but most of the money in marketing goes to execution. And frankly, I’m not sure how valuable concepts and research skills are to a person who doesn’t actually know how to do marketing. In our hiring, we have found that we are best off training entry-level candidates as if they know nothing. If we are starting with that assumption, why do we require a degree?

The philosophy of apprenticeship puts priorities the other way around. In an apprenticeship system, education is an essential ingredient, but it is directly connected to what workers and businesses need.

Apprenticeship vs. Internship

One assumption I often encounter is that professional apprenticeships are equivalent to internships. There are similarities, but understanding how they differ is helpful towards appreciating the impact of apprenticeship. Below are a few key differences.

The applicant pool

- Most internship programs recruit from local schools or rely on students reaching out for internships. Since internships have the reputation of being short-term and poorly paid, they tend to attract students who can prioritize resume-building over bill-paying.

- Apprenticeship programs recruit via workforce agencies and other organizations that have a mission to serve underrepresented groups.

The path to a living wage

- Internships may sometimes lead to offers of employment, but more often they do not. In marketing and advertising, unfortunately, some employers treat internships as a source of cheap or free labor.

- An apprenticeship is a job. If the apprentice progresses according to goals and expectations, they will move up in terms of income and responsibility.

Training and education

- I’ve heard of internships that included structured training, but I’ve never encountered one in marketing and advertising. On the good end they include some amount of mentorship. On the bad end the intern is figuratively or literally ‘licking envelopes’.

- Apprenticeships always include structured training, and professional apprenticeships generally also require some classroom education.

Length of employment

- Internships usually last for a few months, corresponding to a school semester or summer break. Often, employers don’t even refer to interns as employees.

- Upon completion of an apprenticeship, there is usually an opportunity for continued long-term employment.

These are some of the practical differences, but in my opinion the most important distinction comes down to this: who is taking the chance?

If you come from an affluent, educated background, you probably didn’t take many big risks on your way to a career. Most likely, you either chose a career path during your education and started building your job qualifications while you were still in school or you got a liberal arts degree and spent a few years after school figuring out your path while working at whatever job you could get. This describes me and the majority of professionals I know.

If it describes you too, put yourself in the shoes of a person who did not grow up with financial security or a peer group on a professional path. For that person, every job taken and every dollar spent on education constitutes a risk. They do not have your safety net, so they have to be more careful about the chances they take. The wrong job or school choice might put them on a path they literally can’t afford to change. This is not just hypothetical for me. As I have gotten to learn about the lives of prospective apprentices, I’ve heard real horror stories of bait-and-switch jobs and costly certification programs that promise security but deliver debt.

So, how does that person feel about an internship that holds no promise of what comes next? I can’t really say, because they have already shown the courage to take chances I never have. To them, perhaps an internship is another opportunity, but it is an opportunity that comes with little to no commitment from the employer.

In a sense, you could say that an apprenticeship is an internship with a shared commitment to training and gainful employment.

As an employer, making that commitment is taking a chance. You may invest in an apprentice that doesn’t work out. But if you want to create a more equitable and productive workplace, shouldn’t you be willing to share risk with the person you hire?

Our Experience

We hired our first apprentice nine months ago, and our second just this month. While developing the apprenticeship, I spoke with a variety of people and organizations that have created professional apprenticeships in the US. I also work closely with a marketing agency in the UK that has a robust apprenticeship program. From my experience, the risk is actually fairly small.

Prior to starting our apprenticeship program, we wrote job descriptions that “weeded people out”. I include quotes here, because it is something I’ve heard many hiring managers say. The idea is that by stuffing your job descriptions with specific and often unnecessary requirements, you will narrow down the applicant pool and make the job of hiring easier.

The goal of apprenticeship is to minimize prerequisites, so we found ourselves examining what it takes to be successful at Two Octobers. The attributes we zeroed in on are curiosity, collaboration and impact. We then developed screening questions related to these attributes. When you focus on attributes rather than credentials, the hiring game changes. For our recent hire, I interviewed three candidates that exemplified our attributes and several more that I would have hired had the field not been so competitive.

It turns out that there are a lot of amazing people out there that I would never have met if we hadn’t done this.

Getting It Done

Apprenticeship addresses key challenges and finding good apprentices is not hard, but what does it actually take to create an apprenticeship?

Our apprenticeship is registered with the US Department of Labor, and I recommend you consider the same. Developing a Registered Apprenticeship unlocks a variety of resources. In particular, local workforce agencies are eager to support certified programs (here’s a resource to find an agency near you: https://www.naswa.org/membership/workforce-agencies).

We have received a ton of help with hiring and supporting apprentices. And a Registered Apprenticeship may also qualify candidates for federal and state financial assistance with the educational portion of the apprenticeship.

A Registered Apprenticeship has two key ingredients:

- On-the-job training – this is not any more complicated than it sounds. You need to outline the training the apprentice will receive.

- Related instruction – this is the educational portion of the apprenticeship. Because our program only requires a high school diploma or GED, we included college courses in business math and writing and various other topics and skills in our related instruction. We designed a portion of it around our local community college system and a portion of it through Coursera. My criteria for what should be included in related instruction is this: what will help the apprentice become a well-rounded and successful professional long-term? Our goal is not to create indentured servants. We would like for them to stay on with us once they are done with the apprenticeship, but we also want them to have the confidence and skills to succeed anywhere.

The paperwork for getting a Registered Apprenticeship approved is comparable to applying for a loan. It’s not nothing, but nor is it a huge amount of work. We also had help from several apprenticeship consultants who work for the State of Colorado. Many states have resources dedicated to supporting apprenticeship programs.

Actually designing and implementing the apprenticeship is where the work is. We had the benefit of a pretty well-developed training program when we started, but we have continued to put a lot of work into it as the apprenticeship has evolved. Having well-defined training is good for all of our employees and clients, but the effort to develop and maintain it has been considerable.

Apprenticeship changes lives, and fixes a broken system

What started as a conversation about a recruiting challenge for Two Octobers became so much more. By recognizing structural inequities in our industry, and learning from existing models abroad and in the US, we identified an opportunity to create a professional apprenticeship in digital marketing. In so doing, we are providing a pathway to fulfilling, well-paying marketing careers for curious and collaborative people who might not otherwise find this path.

When I started this process, I told myself that changing just one life would make it a worthwhile endeavor. I still think that’s true, but it’s not the right way to look at it. We are not doing our apprentices a favor. As my friend said, our system is broken, and apprenticeship provides a solution that benefits employers every bit as much as employees. By opening up our talent pool, we are able to grow faster and stronger. More diversity on our team makes us better at marketing, which in turn helps our clients grow.

Nico Brooks is a principal at Two Octobers and an adjunct professor at the University of Denver. In college, he studied mathematics, which qualified him to be an actuarial or go to graduate school. Instead he chose to become an apprentice furniture maker. After a circuitous path, he ended up co-founding Two Octobers. Two Octobers is committed to progressing apprenticeship as a means of repairing our broken system. If you hire marketers and would like to learn more about our apprenticeship program, please reach out.